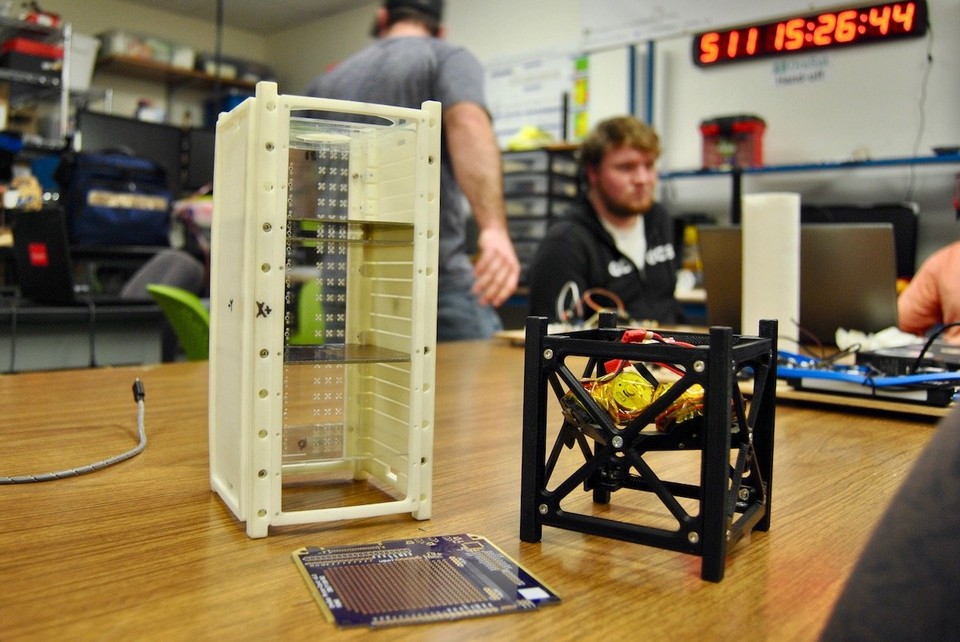

In the basement meeting room of the Portland State Aerospace Society, a red digital countdown clock marked the 511 days, 16 hours, 27 minutes and dwindling seconds until Oregon’s first nano-satellite is due for a hand-off to NASA.

During their weekly meeting on Friday, 11 members of the nonprofit society discussed progress on the creation of the tiny cube satellite they’ve dubbed OreSat.

OreSat will spend between six months to a year in low Earth orbit on a primarily educational mission. During that time, the satellite will be able to point at participating high schools and beam back live video images from space, creating what designers call “a 400-kilometer selfie stick.”

That’s if everything goes to plan.

At this stage, it’s a big if.

Andrew Greenberg, adjunct professor at Portland State, is leading the OreSat effort for the aerospace society, whose membership he describes as “amateur rocket hipsters” and “open source space nerds.” Though the aerospace society has historically focused on rockets, they’ve also spent the past year working on OreSat.

Cube satellites are modular nano-satellites – generally no bigger than a bread box – that can be used for observation or research. Oregon’s will measure just 10 centimeters by 10 centimeters by 20 centimeters. In addition to educational aims, OreSat will map high altitude cirrus clouds in an effort to better understand their role in climate change, and also test a Wi-Fi signal from space.

In November 2016, Greenberg applied for NASA’s Cube Satellite Launch Initiative, which offers to send educational and nonprofit research projects into orbit. He proposed to launch “An Artisanally Handcrafted Satellite from the State of Oregon.”

NASA, he said, didn’t appreciate the Oregon joke, but they did like the application. OreSat was one of 32 educational cube satellite projects approved for the initiative in 2017.

NASA will give OreSat a free ride to the International Space Station. From there, it will be shot out of the side of the space station to begin its orbit. OreSat will begin falling back toward Earth, but moving at such a high speed that it will pass some 4,000 times around the globe before it descends and burns up in Earth’s denser atmosphere.

“We’re a year and a half away,” Greenberg said. “Fall 2019 for launch, which means summer 2019 for hand off, which means fall 2018 NASA will come up to us and say ‘Which of these flights would you like to be on?’

“It’s coming up really fast, which is why we’re freaking out.”

The team working on OreSat consists mainly of students but also of current and retired engineers interested in space science. Among them is Ed Steinberg, a retired engineer who got his start working on missile guidance computers for Raytheon.

“It’s important for student development,” Steinberg said of the project. “We want to have more people involved in math and science. If you look at the numbers, we’ve been lagging behind as a country and also as a state. The idea is if we come up with exciting things that begin to captivate people, they’ll get interest.”

Following the excitement of the 2017 solar eclipse viewable over Oregon, Greenberg hopes OreSat will get kids interested in orbits and satellite tracking. For less than $50, schools will be able to construct their own mini ground stations to receive information from OreSat. The hope is to reach places in the state that don’t often have access to space projects, from East Portland to rural East Oregon.

“Maybe some (students) will go into science, maybe some will go into engineering,” Greenberg said. “Maybe some will never do that but they’ll have the experience and have a deeper understanding of these things.”

Steinberg was a high school student in the early 1960s. From his phone, he pulled up an old photo showing him with members of his high school rocket club posing at an artillery range.

“We used to build our own rockets and mix our own fuels and fire them off,” he said. “At that time, the Army wanted more people to get involved with rockets because of the Soviets and the Cold War.”

He pointed to the kids in the photo. He became an engineer. Two of the boys became chemists. One girl became a pharmacist.

Today, how many science careers can be inspired by a satellite the size of a shoebox?

While the space ride is free, builders must come up with their own cash to create OreSat. Donations to the Portland State Aerospace Society are tax-deductible, and the group has begun contacting corporate sponsors for the project. Greenberg hopes to raise at least $150,000 to construct three satellites: a development prototype, a flight version to shoot into space and an engineering version to keep on the ground.

At first blush, that seems expensive for something destined to disintegrate in the sky. Why spend money on space when we’ve got plenty of problems to address here on Earth?

Greenberg takes some inspiration from the space nerd canon of Star Trek.

“There’s this dichotomy, which is if you look at what’s happening right now, it’s awful and terrible, and if you look at Star Trek it’s amazing and utopic,” he said. “There’s this idea that we can go towards that, that there’s an amazing future for us as technology and humans develop.”

Scientific endeavors that aim for the stars bring us advancements here on Earth. Technologies developed by NASA have given us camera phones, CAT scans and LED lights. Who knows what’s next.

“I hope there is some link between the technology and dreamy stuff we do on this end that helps with the day to day,” Greenberg said. “I’m not sure that’s true, but that’s the hope.”

— Samantha Swindler is a columnist for The Oregonian/Oregonlive

@editorswindler / 503-249-4031

sswindler@oregonian.com

Source: http://www.oregonlive.com/portland/index.ssf/2018/01/oregons_first_nano-satellite_o.html